Climate & queer justice are fundamentally intertwined. A queer story of imagining and building a regenerative world

Misha D. Clive (they/them) serves as Vote Solar’s Digital Director. Celebrating LGBTQIA+ Pride Month, they explore how queer resilience and creativity is intertwined with a just vision for climate. Part of a series: Vote Solar Staff Voices

Building a regenerative world where everyone can thrive is an act of creativity and imagination. How do we dismantle the toxic, extractive world we came into and create a new way forward?

Re-imagining how we want to live and thrive in a just energy world is a journey I walk full of queer energy. Our queer power is essential in an era that requires radical transformation and liberation. We envision and build chosen communities of care, where we can be who we are and love who we love.

The movements for climate justice and queer justice are fundamentally interwined, and many of our LGBTQIA community members, are on the frontlines of the climate crisis. Queer people are everywhere, and climate impacts us all. And people living at the intersections of structural oppression based on race, class, gender and gender identity, and disability are the same people who are among the most vulnerable to the burdens of pollution and the dangers of a changing climate.

Today, I live with chronic illness pushed to the extremes by our toxic environment, and I wouldn’t survive this without queer resilience and creativity.

Within queer spaces, we are constantly examining and redefining the concepts that frame our collective understanding of self and our relationships to others. In my queer life, one of the biggest shifts I have experienced is how certain pockets of our culture explored gender and flowed our learnings into the broad movement for just progress.

Experiencing this shift personally has shown me a glimpse of what a better world could be.

The road to where?

I began my journey to a life of activism as a queer teen in the late 90s, when being myself in community felt entirely like an exercise in imagination.

I was born into an oil and gas world with the price of filling up the tank as a big hot topic, and the U.S.’s oil interests in the Middle East driving acts of war. My best friend’s family were solar installers, who had been in solar since the 70’s. It prompted me to wonder if there was somehow a way out of this mess.

When I came of age, I decided I would not learn how to drive or own a car, because I wanted to limit how the money I would someday make would support the fossil fuel industry. I knew that any personal climate choices I was privileged to make were a drop in the bucket, and one day I wanted to help change the whole system that had made the car of the moment the gas-guzzling SUV.

At the time, I lived in constant terror of losing my friends or being demonized for my whole life by religious extremists who saw me as unworthy of essential rights. I could only dream of taking a nice walk holding hands with someone I love if we would be perceived to be queer, or living authentically to my gender not just in my personal life but in my future professional life.

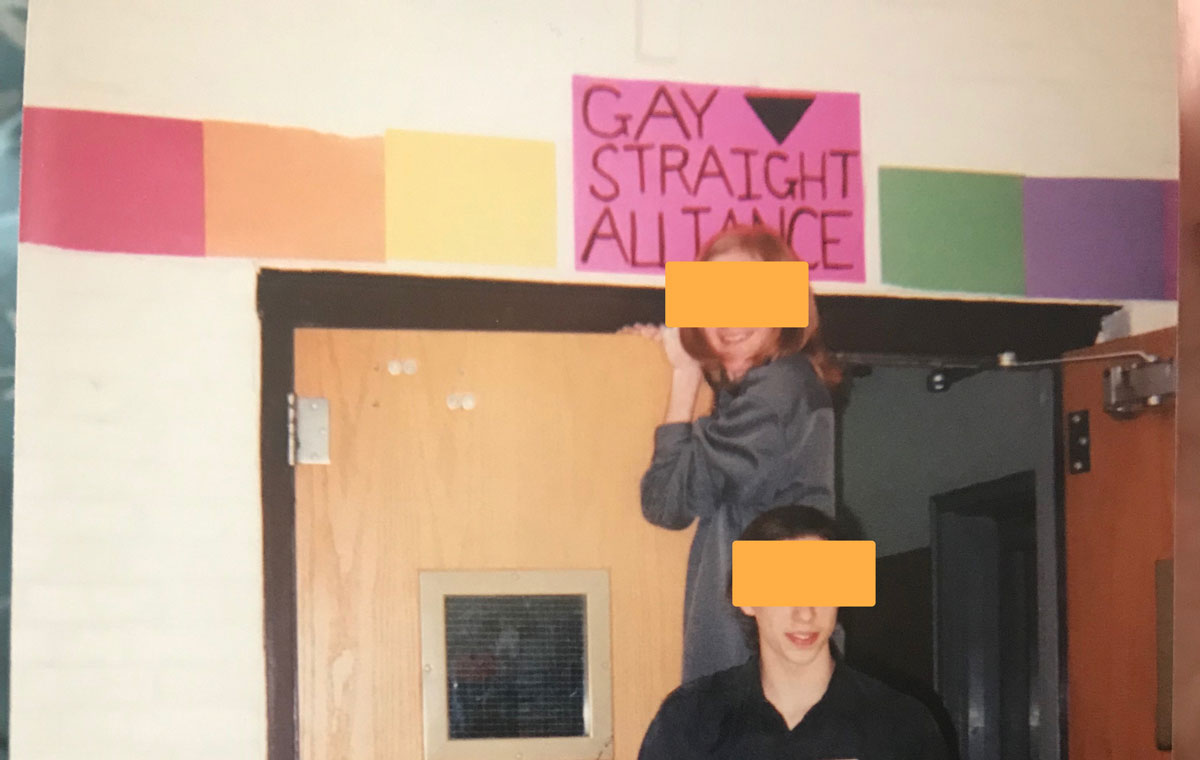

Determined to live in a world like that one day, I founded my high school’s Gay-Straight Alliance and came out in the school newspaper as “gay,” which seemed like the strongest statement at the time. My teachers were alarmed and called my parents to make sure they were cool with it. Too many queer teens faced being cast out by their families and hid their true selves. I was fortunate to have been raised by civil rights activists who were proud for me to take a stand, and have the privilege to be a voice when others couldn’t take the risk.

As I organized tirelessly for queer rights from then through college, over time I came to recognize myself as belonging somewhere within the umbrella of transgender identity… but where?

On the road to self-discovery in the 2000s, I often went to a major annual health conference in Philadelphia for transgender people and allies. This convention that grew to thousands of attendees was the largest gathering in the U.S. aimed at the transgender community that I knew of. I looked forward to it every year for the opportunity to step into a world where our experiences with our bodies and identities were the norm, not the outlyer. But I still often found myself feeling isolated.

At the time, the programming was split between serving trans men and trans women. The ideas dominating transgender narratives at the conference were transitioning identities — FTM, female-to-male, MTF, male-to-female. These acronyms centered a social and medical transition trans men and women were making to be seen and recognized for who they were, from one side of a female-or-male gender binary to the other.

There were no sessions for people who hadn’t arrived at a binary concept of their own identity.

Under the surface, I shared a fundamental experience with trans men that had blocked us all from living fully as our true selves. The world we were born into had assigned us the label “female.” As we were raised and socialized, we were told in countless spoken and unspoken ways that we were “girls,” and then “women.”

But I wasn’t sure if I was a man. All I had arrived at back then was that I was definitely not a woman. Once I was just a young kid who loved sundresses, Hot Wheels, and legos, and wanted to be an astronaut. I looked up to Sally Ride, not because she was the first American woman in space, but because that didn’t stop her from reaching the stars. From the first moment I realized people were gendering me, I felt uncomfortable in my body and dissociated from the idea of having one at all. It was easier to be sure of what felt wrong to me than to know what was right.

Female-to-what, exactly…?

The conference programming told me that if I was leaving behind female, then my destination must be male. At the time, I felt I had no choice but to try to embrace an FTM identity.

Because if I wasn’t a man at the biggest trans event I had ever been to, there was literally nowhere for me to go.

Stepping into the new world

By that time in the 2000s, I was organizing against the Iraq War and the big oil interests behind it. Anti-science propaganda was everywhere, blocking real climate progress, while renewable technology was starting to rise as a real path forward to a future without the immense cost to human health and lives perpetrated by the fossil fuel industry.

I wrapped myself in rainbow flags at protests, which were a common sight, among many other symbols of a movement of people who could see the connections across intersectional issues.

The same arch-conservative voices peddling anti-climate narratives also kept spreading lies that demonized our LGBTQIA+ community. I helped to kick one of those Senators out of Congress, who was a major roadblock to ever reaching a healthy nation. But as I fought for queer rights, I kept trying to find where I belonged in my own queerness.

One sunny summer day in Philly, in the midst of figuring myself out at this big trans conference, I came out in a whole new way.

I arrived to my first session in a fabulous mood, excited to be back with my people. I wore a stylish red jacket with decidedly femme flair, and my long hair up in a high ponytail.

And wow, did I stand out.

The room I walked into that morning was another FTM-centered session, packed with people who were likely there because they were indeed trans men. And the particular folks in this room also shared a common style in how they looked and dressed. Short or buzzed hair, baseball caps, athletic or casual everyday men’s wear in neutral or sportsy colors. The gender expression was stunningly uniform.

I’m the least masculine-presenting person in this room by a mile, I thought, and I was tempted to run and hide.

I felt lost in trans spaces that were like this, out of place among those who had what seemed to me like a concrete path on this gender journey. Yet I still felt bold.

I raised my hand near the end of Q&A and the presenter called on me. Nervous but determined, I asked, “Is there room for being femme within FTM identities?”

“That’s… a very good question.” He used the classic stalling tactic when you’re not sure how to respond—I use it all the time. After a long pause, he said, “I don’t have an answer for you, but I’ll think about it.”

After so long fighting for our rights and seeking out queer and trans community, I left that year’s conference feeling more alone than ever. But I continued to join many others who kept raising our voices and experiences from outside the gender binary at this seminal event.

Cut to years later.

It was another summer day, and I was in a room again at this same conference. Only now, I was living in a whole new world.

The chairs had started out in a tiny gathering, but we had to band together to spread them out in a circle that lapped the entire room. Hundreds of people packed the space… and we all came here to talk about being genderqueer or outside of the binary, and what it mean to us.

There were genderqueer and genderfluid and non-binary people, femmes, butches, androgynes, people who identified with ideas of gender from cultural heritages outside of Western colonizing hegemony. And there were trans men and trans women, comfortable allies or questioning. People of a true rainbow of gender expressions, perspectives, and journeys as to how they arrived there in that circle.

Here, I could be. Here, I could thrive.

I was home.

So this was what it was like to build a new world.

Around the same era of my life, I traveled with my brother to the Mojave Desert in California and saw my first wind farm. The beautiful turbines dotted the skyline. In the genderqueer space of the Philly conference, I was among liberated bodies, and amidst the power of renewables, I could see the way to turning the tide on climate.

Building restorative community

With a fresh queer fire in my heart, I went on over the decade to build local queer and trans community and safe spaces for more people to discover themselves and feel safe who wanted to be in gender expansive kinship.

Within these spaces, no one ever assumed my gender and pronouns, or anyone else’s. Every room we made together was an open canvas of being. Everyone was welcome, trans or cis, socially or medically transitioning/transitioned or not, genderfluid or not, under the queer umbrella, curious, or allied.

This act of leaving the basic architecture we’re given aside and building our own is a shared experience of reinvention in queer community. Our relationships tend to be less conventional, and more attuned to the people in them.

In this queer space where my spirit lived, we could talk openly not only about the constructs of gender and relationhips that we were redefining, but about every aspect of our mental and physical health while struggling to make it in a larger society that wasn’t designed by us.

Together, we created our own little world, shaped in the image of how we wanted to live as our whole selves. Not only defining for ourselves what gender and relationships and family could look like, but also a place where we chose care and compassion over the brutal urgency and commodification of our lives under capitalism.

Throughout this time, as I fought for intersectional justice, against Big Oil, for immigrants’ rights and living wages and healthcare for all, I kept going on queer issues, speaking out on the intersections of queer rights and disability justice, serving trans women of color in their leadership and centering them in the movement, fighting for marriage equality, and on and on. We’ve come a long way, but we have a long long ways to go for queer rights, safety, and liberation.

Along my own journey, I decided to take my climate-centered activism to the next level at Vote Solar. More than anything else, my community building for genderqueer spaces motivated me to arrive at Vote Solar expecting everyone to respect my pronouns and my relationships. Not only did my peers respect me, but today I’m proud to say we have a fierce and significant squad of LGBTQIA+ folks on our team who are putting in the work every day for a just climate.

And today it’s become far more common in the non-profit and impact community to ask for instead of assuming pronouns, to make space for non-binary and genderqueer identities, to recognize folks like me who go by they/them.

At Vote Solar, I’ve been privileged to serve communities that have been intentionally excluded from power over their energy choices by the racist, classist fossil fuel system of over a century. Polluting industries have bombed communities of color and low-income communities with toxic emissions, causing diseases and cancers, and shortening life spans. We follow just partnership principles as we work with local leaders and organizers to center their wisdom and leadership in designing a way forward from the climate crisis, through the policy and regulatory transformations that make it possible.

Between the old world and the new

As we all worked together over this past brutal year the pandemic stretched around the globe, I became severely ill from an environmentally-acquired illness that gave me an autoimmune disorder out of control.

Autoimmune disorders are increasing as we add more toxic pollutants and practices to our environment, disproportionately impacting communities of color on the frontlines of the climate crisis. From pesticides and industrial agriculture to the dangerous toxins building materials to the toxins exposed through extreme weather, we’re on the road to more and more complex illnesses that make our immune systems go haywire and make everyday living a nearly insurmountable challenge.

In my case, my body started reacting to pollutants, plastics, nearly all foods from our industrial system and anything but the cleanest air and water with disabling numbness, vibrations, pain, and nausea. I couldn’t wear clothing with plastic fibers, or eat almost anything without getting sick. Between COVID and my own illness, it wasn’t safe to go outside, and it wasn’t safe to stay inside. I had no safety but the wonderful partner I had in my life, and my own queer resilience. To this day, I still have to stay within severe restrictions just to function.

As I write this now, my partner and I are only just getting to emerge from a year of being severed from that queer community we were deeply part of. That resilience I’ve built from years of striving for a better, whole life and imagining what a healthy new future could look like has helped me make it here through the struggle.

In the queer spirit, when we’re trapped within the oppressive world that tries to drain us of our queer energy, not only do we fight for liberation, but we create our own communities where we don’t have to wait to achieve it. Queer imagination is always a source of inspiration for me in envisioning a 100% equitable clean energy future, where we end the harms of over a century of fossil fuels and a power structure designed to disadvantage and harm communities nearest the sources of pollution.

Communities who are the most impacted by environmental illness are leading on climate solutions, including LGBTQIA+ leaders working at the intersections of race, environmental justice, health and disability justice, and queer and trans rights. Through my work at Vote Solar, I have learned so much from their wisdom and resilience on what a fully realized, racially just and regenerative world could look like.

I’m living in a liminal place between the toxic old world and the bright new future. I’m proud to do my part to transform this extractive world into one that is restorative, healthy and just.